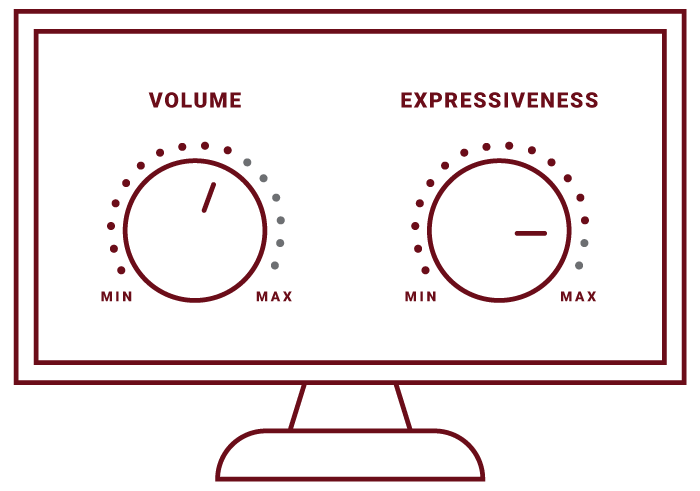

How loudly to speak is one of the most important and revealing choices you can make on camera. Volume — perhaps more than any other dynamic — ultimately reveals whether you’re interested in connecting with your audience or just performing for them.

Few news talent manage volume as deliberately and effectively as NBC New York’s Chuck Scarborough. In the clips featured here, he communicates with a specificity and nuance that would not be possible if he were speaking louder and relying solely on the sound of his voice — which is beautiful and can command attention in its own right. Instead, he chooses a level that invites viewers closer as opposed to pushing them away.

The level also enables him to manage pace (note where he chooses to slow and pause) in a way that underscores the issues that are specific to the stories he’s sharing. His delivery is appropriately urgent when necessary, but never rushed. The volume facilitates the pace, and the pace invites us to understand and to think about the story. He connects us to stories, as opposed to simply proclaiming the stories.

Jenni Steck, our go-to voice and speech guru, points out that all of this is just as important when you’re tracking as it is when you’re on camera. Here’s another clip, this one featuring CNN reporter, Sara Sidner. It’s great example of how expressive and connected you can be, even at a low volume.

In her book, The Second Circle, world-renowned voice coach Patsy Rodenburg explains that you fundamentally have three choices when you project your voice.

Too soft

You can project with an energy that is self-contained and does not really reach the listener. Rodenburg terms this area the “first circle” — that area immediately around you that doesn’t really contain anyone but yourself. When your voice and related energy fall back and don’t compel any attention from the viewer, you’re speaking into that first circle and not beyond it.

Steck points out that this also has the effect of putting the burden of the interaction on your viewers, in effect forcing them to work harder at connecting than you are. “Chances are, they’ll be done with you pretty quickly,” she says. “They’ll find something or someone else to watch. You’re too much work!”

Too loud

You can project with an energy that is intended to demand attention but not really intended to connect in any way. It is a volume and energy that goes past the viewer and into a space beyond her, which Rodenburg terms the “third circle.” When your voice and related energy are bgger and louder than necessary to reach the viewer, you are speaking into that third circle. It is a volume and energy that seeks to dominate. It has little to no interest in the reaction or identity of the listener. It just wants attention.

“In this third circle,” Steck points out, “you are talking at me, not to me.”

Just right

The “second circle” is Rodenburg’s term for the distance of real presence and connection. You use the exact level of volume necessary to reach your viewer. It is the volume level that signals your interest in the other, because it is calibrated by an awareness of the other — how close he is to you. it is the only level at which viewers really feel you have any sincere interest in them, as opposed to just wanting them to pay attention to you.

On television, the key to speaking to viewers at the distance of connection — the second circle — is adjusting your volume to the distance of the shot, as opposed to speaking to the distance of the camera or trying to fill the size and emptiness of your environment. The camera, for instance, may be 10-20 feet away, while the viewers may be seeing you as if you are only 3-5 feet away. The room may feel large and empty to you while the shot feels close and intimate to them. If you’re going to connect, you have to calibrate your voice to their experience and not your own.

Steck again: “It’s a mind trick! In the field or in the studio, your brain registers that you should project your voice to reach the camera. The same thing happens when you are in a location with background noise that you hear but the audience does not. In both situations, your brain tells you to be louder. You have to remember that your microphone is right there! You don’t need to push.”

For many people, this is not as easy as it sounds — probably because the lack of any observable reaction from the camera kicks their voices reflexively into overdrive. They subconsciously get louder and faster and higher, just the way a child gets louder and faster and more shrill when she can’t get the attention she wants from a parent. Steck says this all creates a frantic or frenetic energy, instead of the ease and relaxation that would project authority and confidence.

For human beings, nothing is as disconcerting as being ignored and treated with indifference, and nothing is as indifferent as a camera lens.

Here are some recommendations that may help:

Study the way you communicate in “real life” when you are in conversation at close range about something that matters to you. Most of the people we coach become animated and alert, leaning toward us, gesturing and speaking at just the volume they need to “land” their words on us. No louder and no softer.

Use the real people around you to calibrate your volume for the camera. If you have a coanchor or other colleague sitting close to you on set or near you in the field, spend a few moments speaking to them naturally and easily, then turn to the camera and attempt to keep the same level.

Remember that reduced volume does not necessarily mean less animated. In fact, in conversation talent frequently become more animated when they are concerned about making a point and really feel the need for us to understand it. And isn’t this the way an anchor or reporter should feel when they share a story with viewers? Like they have something important to share and really feel the need for viewers to understand it?

If it’s difficult for you to tease apart volume and energy, Jenni has this suggestion: “Try speaking loudly and forcefully, with lots of expression. Then just lower your volume but continue using your body just as expressively. The body must stay active and alive. We’re only adjusting the volume.”

Imagine you are talking at close range to someone you care about — and that cares about you. One fundamental truth of human communication is that the way we express ourselves changes profoundly based on who we believe we are talking to, as well as the distance at which we are addressing them. On television, the audience is always a figment of your imagination. It is important to imagine it in a way that brings out the best in you.

This is not to say, of course, that you should never project. There will certainly be moments in almost any newscast that may call for something more or something different. And with volume, as with every other delivery dynamic, variety is really the key to working effectively.

It is to say that you cannot manage volume levels effectively without understanding and mastering them all — especially the level you use when you are interested in truly making a connection.